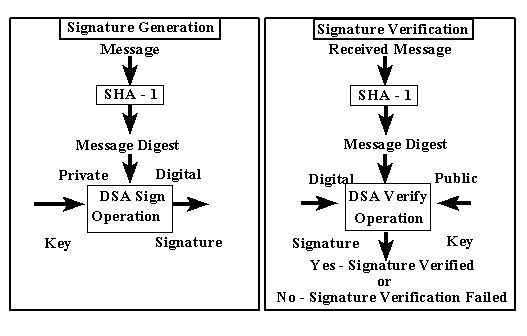

The signature will still be valid because of the collision, but Bob controls key A with the name of Alice, and signed by a third party. “Using our SHA-1 chosen-prefix collision, we have created two PGP keys with different UserIDs and colliding certificates: key B is a legitimate key for Bob (to be signed by the Web of Trust), but the signature can be transferred to key A which is a forged key with Alice’s ID.

In the new research, Leurent and Peyrin were able to show that SHA-1 should not be used for digital signatures, either. That work from 2017 showed that it was possible to create two distinct files that would have the same SHA-1 digest and resulted in the browser manufacturers deprecating SHA-1. The chosen-prefix collision is distinct from the SHA-1 collision developed by a team of researchers from Google and the Cryptology Group at Centrum Wiskunde and Informatica in the Netherlands.

We are not aware of a CA doing this, but it may still exist somewhere.

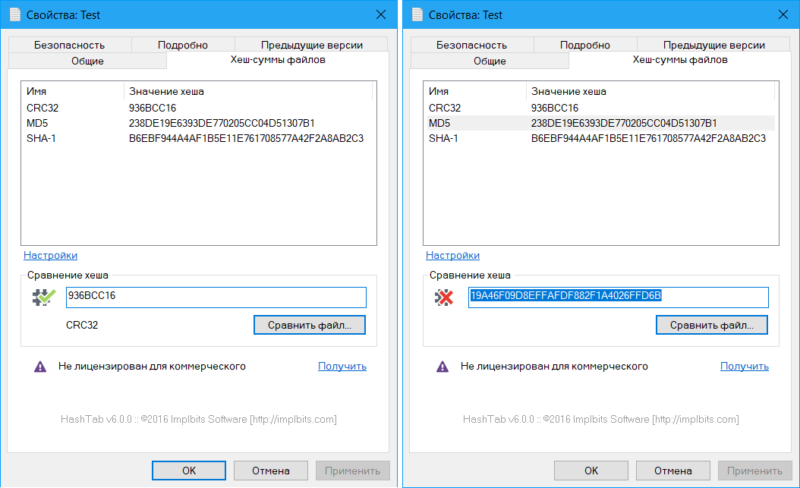

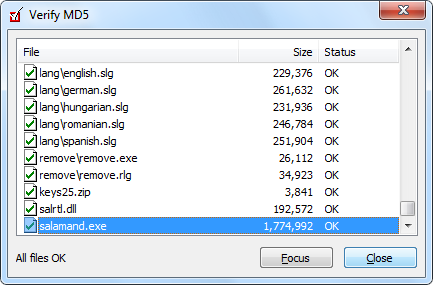

SHA1 CHECKSUM SERIAL

There could also be attacks similar to the MD5 Rogue CA or the attack used by the Flame malware to break windows updates, but that only works is someone is still signing certificates with SHA-1, and using predictable serial numbers. However, the attack is still far from practical in this setting because we need to compute the collision in a few minutes at most," Leurent said in an email. "Another important scenario is the handshake signature in TLS and SSH which were vulnerable to the SLOTH attack when MD5 was supported, and could now be attacked in the same way when SHA-1 is supported. But the researchers said there are other possibilities, as well. There are several potential scenarios in which the new collision could be implemented in an attack, the most likely of which is someone impersonating another user by creating an identical PGP key. “We note that classical collisions and chosen-prefix collisions do not threaten all usages of SHA-1." SHA-1 is the default hash function used for certifying PGP keys in the legacy branch of GnuPG (v 1.4), and those signatures were accepted by the modern branch of GnuPG (v 2.2) before we reported our results.” However, SHA-1 signatures are still supported in a large number of applications. “SHA-1 usage has significantly decreased in the last years in particular web browsers now reject certificates signed with SHA-1.

GPU technology improvements and general computation cost decrease will quickly render our attack even cheaper, making it basically possible for any ill-intentioned attacker in the very near future,” the researchers said in their new paper, published this week. “Our work show that SHA-1 is now fully and practically broken for use in digital signatures. The new collision is the work of researchers Gaetan Leurent and Thomas Peyrin, and while SHA-1 isn’t widely used anymore, it has potential consequences for users of GnuPG and OpenSSL, among other applications. But the new result shows that SHA-1 is no longer fit for use. SHA-1 has been phased out of use in most applications and none of the major browsers will accept certificates signed with SHA-1, and NIST deprecated it in 2011.

The technique that the researchers developed is quite complex and required two months of computations on 900 individual GPUs, so it is by no means a layup for most adversaries. The development means that an attacker could essentially impersonate another person by creating a PGP key that’s identical to the victim’s key. UPDATE-SHA-1, the 25-year-old hash function designed by the NSA and considered unsafe for most uses for the last 15 years, has now been “fully and practically broken” by a team that has developed a chosen-prefix collision for it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)